How can you know where you’re going if you don’t know where you’ve been?

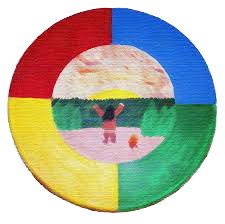

A few weeks ago, I shared this photo on Facebook. Whoever posted it in the first place had given it the caption, ”Early American Art” which I thought was quite clever. I find the art work very beautiful, and one can only imagine the wide range of tipi paintings, the shapes and colours, a whole encampment of them, even.

What saddens me about the photo is that it speaks to a way of life that we are only now understanding the true antiquity of. The discovery of a First Nations site on Vancouver Island a few years ago that dates back some 14,000 years astounded the experts, evidence that indigenous people arrived here so much earlier than previously believed.

Think of that! The pyramids in Egypt are some of the oldest man-made structures in the world, yet they are only 5,000 years old. 14,000 years is a long time, no matter how you slice it. The First Nations of our present day Canada survived and flourished all this time without any of the benefits of European culture. In fact, it only took a few hundred years of contact with the Europeans for this indigenous culture and way of life to come to a lamentable end.

Worse still, I find as I gaze at these images, is the eradication of the history of the people. Being essentially oral-based cultures, the wisdom and the mythology was passed on from generation to generation all those hundreds and thousands of generations by word of mouth. That is a fragile and delicate system, to put it mildly.

Yet even at that, the stories and legends and knowledge were effectively passed down, until there was a terrible break – I am thinking of the Residential School System. We all know, now, thanks to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that the native children in these schools were forbidden to speak their native languages or pray to the god (or creator) of their parents. They were force fed a foreign mythology, their own history ignored, hidden from them..

In many cases when children were released from the schools they could not find their parents, or if they did, the psychological trauma of separation of parents and children was too great to overcome.

And so, then, what happens to history, to culture, to spirituality when there is a break like this and the keepers of the stories have no one to pass them down to, or if they do, they are too damaged to give them fair ownership? Well then, it is gone, all of it, and in many ways is probably irretrievable.

I came up against this last year when creating the script for our film The Road (which can be viewed at theroadfilm.ca for a small fee). I had conceived of the road leading from this distant past into the future. As a discussion and then a writing prompt, I asked to girls to imagine what life was back, say, 1,000 years ago.

They had a lot of difficulty envisioning such a world. I looked around the building we were working in and said, “Imagine this doesn’t exist. And there are no lights. No heat. (It was winter.) No cars to come here in or go back home in. No stores to buy things in. No fast-food restaurants, no 7-11.

For the most part, they couldn’t. They were entirely ignorant of their own history. One girl could. One of twenty-five. She wrote what became the film’s opening scene of being out on the prairie with her grandma, a young girl listening to her grandma’s stories. It made for a beautiful opening to our film. But of course, it was bittersweet to think of all the stories of all the grandmas that have been lost.

Of course, there are keepers of the flame, people wise in the old ways, including our elder Wanda First Rider and others who visit the Stardale circle and share their stories with the girls. With each passing year I believe this return to the oral tradition, passing on the collective wisdom of the people is critical to the survival of our girls and other indigenous people.

After all, how can you know where you’re going if you don’t know where you’ve been?